The global recession is causing widespread suffering and hardship but, in some respects, it may turn out to be a good thing for the future development of our towns and cities. A harsh medicine perhaps, but in recent years the lower value uses which enrich the urban realm have been increasingly squeezed out by the dominance of speculative development driven by easily available finance. The recent drop in land values and the tight constraints on funding is now allowing these uses back into the game. The regeneration framework that 7N Architects is developing for Speirs Locks is an example of how this re-calibration of development forces may begin to facilitate a richer urban environment.

Speirs Locks covers 14 hectares of low grade industrial and derelict land by the Forth and Clyde Canal to the north of Glasgow city centre. The area was a thriving trading centre throughout the nineteenth century but a gradual decline with the increasing obsolescence of the canal was accelerated in the 1960s when the elevated M8 motorway sliced through its links to the city centre leaving a solitary underpass connection.

In recent years, attempts were made to redevelop the area which all foundered as their starting point was to replicate, at a larger scale, the remaining Speirs Wharf building from the 1850s on the opposite side of the canal. By proposing to build on the most valuable canalside land first and as a stand-alone development, the potential of the wider area was destined to be diminished and compromised, unless the fundamental structural and social issues of the area were first addressed. A different approach was needed.

Speirs Locks is one of a series of canal focused regeneration initiatives in Glasgow instigated by the Glasgow Canal Regeneration Partnership (GCRP), a partnership between Glasgow City Council and ISIS Waterside Regeneration supported by British Waterways Scotland. The GCRP appointed Make in 2008 to develop a regeneration framework for Speirs Locks following a competitive process involving local stakeholders. The Make team who developed the proposals formed their own practice, 7N Architects, at the beginning of 2009 and are taking the project forward with the GCRP.

An approach was developed over an intensive ten month process of engagement with the GCRP, local residents, businesses and stakeholders from which the strategy we called ‘Growing the Place’ evolved. The essential premise was that the potential of Speirs Locks would always be limited unless the negative perceptions of the area and its disconnection from the city centre were addressed.

“In recent years the lower value uses which enrich the urban realm have been increasingly squeezed out by the dominance of speculative development driven by easily available finance. The recent drop in land values and the tight constraints on funding is now allowing these uses back into the game.”

‘Growing the Place’ originated from reflections on existing places that had been transformed through colonisation by bohemian menageries of people looking for cheap, off-beat, but reasonably central districts that had a distinct vibe to them. Camden Market in London in the 1970s, Hoxton in the 1990s, and Greenwich Village in New York that inspired so much of Jane Jacobs’ 1961 The Death and Life of Great American Cities, were all places which were regenerated through the way they were inhabited, rather than through any form of planning.

These patterns, which have also been well documented by Jonathan Raban in Soft City (1974), tend to follow a similar evolutionary path. First comes the discovery of cheap, plentiful space that has been overlooked, then the second wave of followers, then the bars and clubs, then the restaurants, and finally developers wake up to the opportunities and move in. At this point the original pioneers are usually long gone due to rising values, but this can be managed and used positively.

Growing the Place aims to replicate this process. A form of accelerated urban evolution, emulating the nomadic colonisation of cities by these specific creative groups, to transform negative perceptions and drive the regeneration of the wider area. It is an attempt to grow a place from the ground up rather than making it from imposed development plans or design codes. A Masterplan is frequently held up to be the solution that will magically transform places for the better, but it is commonly little more than a two dimensional (three if you are lucky) manifestation of a development spreadsheet.

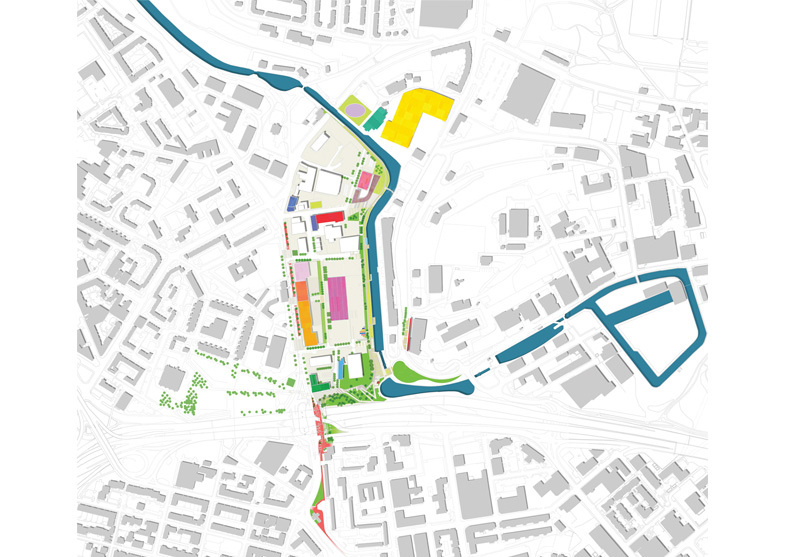

A full Masterplan was produced for the site, to illustrate what the ultimate build-out might be, but it was recognised as a long term framework that might be reached by a process of evolution rather than as a template for specific development. Its main purpose, in the short term, is to provide the big picture that allows the key initial interventions to be identified and prioritised to encourage a diverse range of uses and activities to take root there.

The implementation of the Growing the Place strategy initially focused on two principal objectives: improving the severed connections to the city centre; healing the scar of the M8; and instigating catalyst initiatives to kickstart regeneration, targeting initial investment on a series of limited public realm and arts based initiatives.

The first thing to be tackled was the underpass under the M8 flyover. This new link will be the gateway point - the pedestrian threshold connecting a large area for North Glasgow back to the city centre. It is an extraordinarily hostile environment. Dark, noisy, dirty and intimidating. The proposal widens the underpass considerably, transforming it into a flowing, red resin surface that doesn’t constrain those using it to a single confrontational route. It will be illuminated by a ribbon of coloured aluminium flowers, fluttering 6m up in the air drawing the visitor through the space, in deliberate contrast to the solidity of the concrete and a memory of Phoenix Park that once stood on the site. It is loud, but needs to be to compete with the scale and visual cacophony of the flyover environment and to grab this critical territory back for pedestrians and cyclists.

“First comes the discovery of cheap, plentiful space that has been overlooked, then the second wave of followers, then the bars and clubs, then the restaurants, and finally developers wake up to the opportunities and move in. At this point the original pioneers are usually long gone due to rising values, but this can be managed and used positively.”

This new threshold will connect to a new landscape link that will weave its way up to the canal basin. From this point the whole of central Glasgow is in view as the canal sits on top of one of the city’s many hills. A rather bizarre, but exciting, position for a waterway. There have been many discussions about capitalising on this to raise awareness of the initiatives, including mooring a sailing barge there with an enormous coloured sail to draw the curiosity of the 100,000 people a day who whizz by on the motorway.

On the canal itself, a series of initiatives involving temporary structures to provide low cost studio, cafe and performance spaces are being developed to enliven the canalside with vibrant new activity. These will be nomadic structures, destined to move to other parts of the canal network once their job of revitalising Speirs Locks is finished.

These are some of the initial physical interventions, but it is the growing cultural quarter at the heart of the area that will really make Speirs Locks come alive again. Scottish Opera have been there for many years hidden away in a nondescript shed that does nothing to reveal the richness of the activities that go on within it. The plan was always to try to tap into this, to somehow turn the building inside out so this creativity could energise the surrounding area, but the credit crunch has perversely taken this aspiration way beyond the original expectations.

Plunging property values and resourceful lobbying have encouraged more arts organisations to colonise the existing buildings, attracted by the large footprints and cheap space that they could never compete for in normal market conditions. The Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama (RSAMD) are soon to occupy three of the industrial buildings opposite Scottish Opera for new modern dance studios and production facilities. The National Theatre of Scotland has moved into an existing building facilitated by a favourable rent from ISIS, as have the Glasgow Academy of Musical Theatre Arts (GAMTA). This is already creating a critical mass of cultural organisations giving Speirs Locks a natural momentum as Glasgow’s Arts Campus. A momentum that has come from within rather than being imposed.

7N are currently working with these arts organisations on proposals for the external space in Edington Street between the RSAMD and Scottish Opera. The intention is to remove vehicles and turn it into a flexible communal space that can be colonised for performances, events, teaching and gatherings. It will ultimately be what they wish to make of it, making it special and giving Speirs Locks an essence that cannot be fabricated, but it can be cultivated.

“The intention is to remove vehicles and turn Speirs Locks into a flexible communal space that can be colonised for performances, events, teaching and gatherings. It will ultimately be what they wish to make of it, making it special and giving Speirs Locks an essence that cannot be fabricated, but it can be cultivated.”

By the autumn of 2010 the underpass, the landscape link, and arts space in Edington Steet will be complete ready for the new RSAMD students to colonise them. At that point, when the spaces begin to be intensively inhabited in diverse ways that I hope we haven’t predicted, the regeneration will really have begun. All of the work up to that point will have just been to prepare the ground for this.

The Speirs Locks project, which has been adopted as Supplementary Planning Guidance by Glasgow City Council, was recently designated as one of eleven exemplar projects in Scotland under the Scottish Government’s Scottish Sustainable Communities Initiative (SSCI). The SSCI is concerned with raising aspiration levels to achieve quality place-making and more sustainable forms of development that meet the demand for new homes.

Whilst this positive recognition is encouraging, the project is a long term endeavour that needs to be constantly tuned and nurtured. As is the case with the Camden, Hoxton and Greenwich Village precedents, the issue of gentrification and the social exclusion of existing communities will always be there. Increasing land values are an intrinsic part of the strategy as they are ultimately what will fund it all and pay for the front-loaded public realm initiatives. But the aim is to grow value in the widest sense, economic, cultural and social, and to continually manage and encourage diversity to avoid killing what has created it. The challenge is how to shape these commercial forces in a positive way for the civic wellbeing of citizens and the prosperity of their town or city. This is how successful places have always evolved. It just seems to have shifted out of control around the turn of this century, when things swung out of equilibrium.

It is perhaps too much to hope that the global recession will result in a complete re-appraisal of society’s values, but the world will certainly be a different place after it. A longer term view is likely to come to the fore in the development industry, due to constraints on personal and commercial funding. The seemingly endless supply of credit that fuelled speculative development and large mortgages over the last twenty years will be tightly reigned in for the foreseeable future. This will cause significant shifts in the demand profile and the kind of developments that can be created to meet it.

In the midst of the widespread doom and gloom, the Speirs Locks project may be an indicator of a recalibration of the rules of the development game, opening the door to the kind of holistic approach to urban design that Jane Jacobs proposed in the 1960s. An approach that grows the vibrant diversity of a place from the uses, activities and the people who live and work there, and weaves them into a rich social fabric. Urban design without drawings perhaps.

This article first appeared in Issue 114 of Urban Design, Spring 2010.