The cyclist in the photograph opposite looks understandably anxious about her safety in the midst of all the heavy traffic. She doesn’t particularly look like she is enjoying her journey and it is not a position that anyone would necessarily put themselves in through choice. But consideration of positive choices is becoming critical to the future wellbeing of our towns and cities. As John Lord of yellowbook so perceptively summarised in the last issue of Urban Realm, people now go to places largely through choice where they once used to go out of necessity. The unfortunate dilemma for those with an interest in the civic health of our urban places is that the more freedom and choice that citizens have accrued through increased wealth and mobility the worse these places have generally become. A prime example of this is the current issue of out of town shopping sucking the life out of High Streets. The key challenge facing city leaders is to identify and implement what needs to be done to make people want to go to the city centre in preference to other options.

The shot of the anxious looking woman was taken in Union Street, Glasgow, in 2012 as part of 7N Architects research for the Public Spaces and Neighbourhoods workstream of the Glasgow City Centre Strategy. This forms part of the Glasgow City Centre Vision, an initiative which has the foresight to look at what kind of place the city should be in 30-50 years time. This is a long term view of the city’s needs and aspirations that is not bound by the short term cycles of Local Development Plans and elections.

The workstream forms a major part of the emerging City Centre Strategy. This is intended to provide a tangible manifestation of the vision that will help to guide and co-ordinate planning policy and development within the over-riding context of a holistic vision for the city centre’s future. In this sense it should be viewed as the ‘big picture’ of what Glasgow wants to be, to inform individual projects and initiatives in a way that builds the common vision in an integrated, progressive and inspiring way.

Glasgow has delivered many successful initiatives in recent years such as the regeneration of the Merchant City and the promotion of the Style Mile which has helped to boost the city’s profile as a top retail destination. However, the city is now at a point where opportunities for further improvement will be constrained by inherent issues associated with the city’s infrastructure, unless significant measures are implemented which are bold enough to tackle them. The key challenge is that most of the streets and spaces in the city centre are dominated by motorised vehicles which inhibit opportunities for enjoyment of the city. This is exacerbated by the tight grain of the city centre grid, which makes it difficult for people to freely move around due to the frequency of junctions, the lack of green space, and the way in which the city centre is disconnected from surrounding neighbourhoods by the M8, the River Clyde and nature of the urban form to the east.

Collectively, these issues significantly affect the potential for placemaking as they discourage human activity in the public realm. This activity is critical for cultivating positive regeneration and development, on the principle that good places attract people, people attract more people, and more people drives demand. Although these issues are mainly related to movement, they can be viewed as being symptomatic of the environmental health of the city and how citizens and visitors perceive it. Such perceptions are critical to Glasgow’s future economic and social wellbeing as they directly shape people’s decisions to live, work, visit and invest there. For the Glasgow to move forward and effectively compete, there needs to be a fundamental shift in the balance between motor vehicles and pedestrians and cyclists to significantly improve the quality of experience of city centre streets and spaces and its connections with surrounding neighbourhoods.

“The Glasgow City Centre Vision is an initiative which has the foresight to look at what kind of place the city should be in 30-50 years time, a long term view of the city’s needs and aspirations that is not bound by the short term cycles of Local Development Plans and elections. ”

Our approach to the workstream strategy balanced experiential assessment of the city centre’s streets and spaces with an analysis of the key elements of the city’s structure which critically impact on the day to day experience of those who live, work and visit the city. The key questions were; How does it feel to be in this space? What makes it feel like this? What could be done to the structure to make the experience at street level feel better?

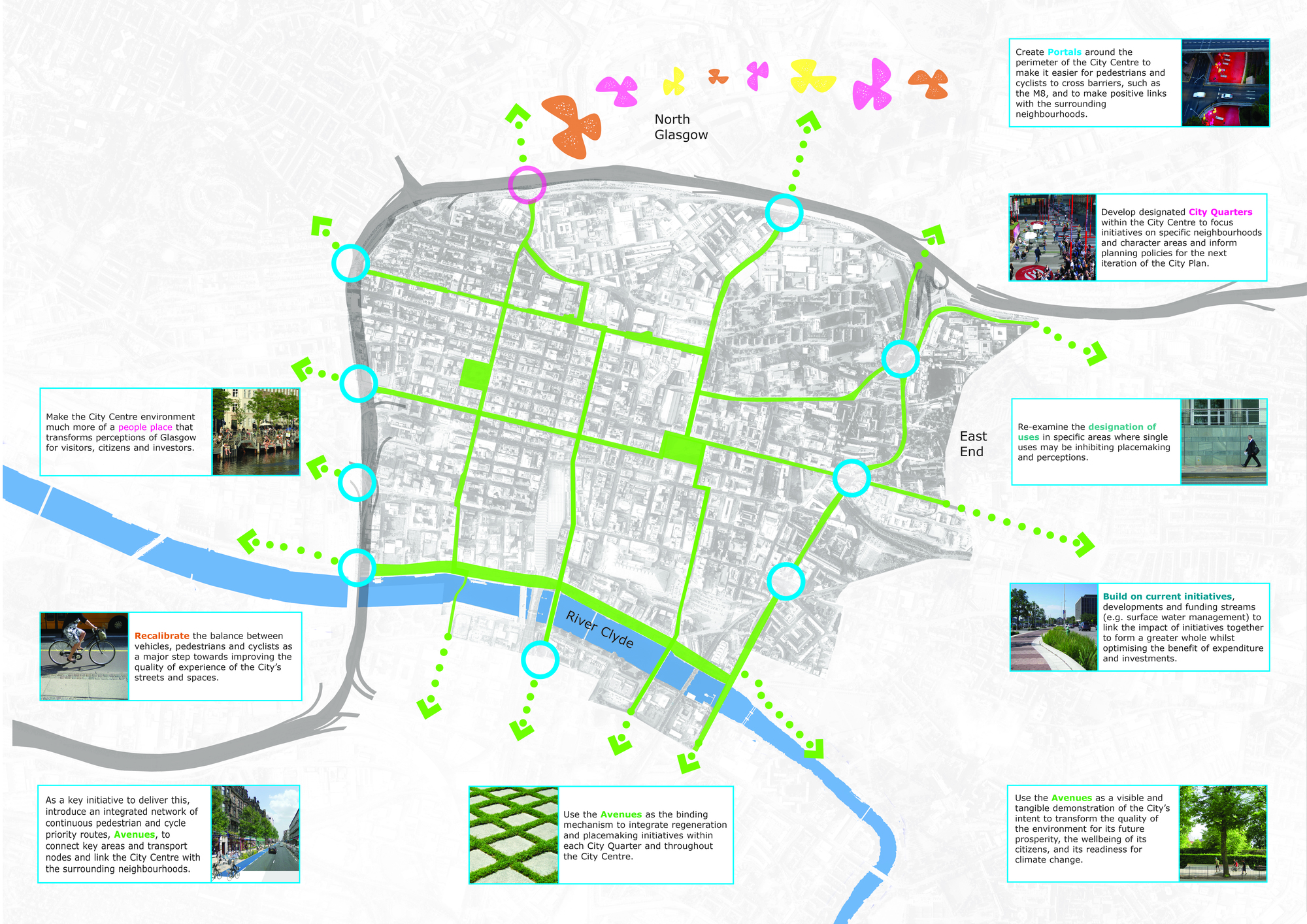

The findings were developed into a series of mapping diagrams of Glasgow which examine particular aspects of the city that influence perceptions of the urban environment. These explored themes such as arrival points, connectivity within the city centre, connectivity to surrounding neighbourhoods, magnets and footfall, perceptions of the identity of areas, activities and uses, and quality of experience during the day and night. Overlaying these diagrams helped to build up a rich picture of the city centre that opened up ways of approaching the structural issues.

A particularly clear outcome of this process was an identified range of issues associated with a lack of physical connectivity, which have a significant impact on placemaking. For example, the city centre has a very defined physical boundary, created by the barrier of the M8 motorway. The motorway, combined with the Clyde creates the impression of a ‘walled’ city that is disconnected from the surrounding neighbourhoods where the majority of its citizens live. Within this ‘wall’ there are clear disconnections between principal arrival points and the key magnets, in terms of poor experiences between them. It was also clear that there is a mis-alignment between how areas were currently zoned, for planning policy purposes, and the much fuzzier mental maps of how people perceive them. Critically, unlike a planning policy zone which generally ends at the midpoint of a street, our proposed mental maps overlap and fade between city quarters and treat streets as spaces rather than edges.

The approach to developing the strategy therefore focused on connectivity and continuity as a primary means of overcoming such barriers and using it as the principal medium for delivering the necessary shift to a people priority place. Getting more people and cyclists to use the city’s streets and spaces needs continuity to facilitate the ability to move freely and safely around the city.

The strategy was developed as a series of key principles structured around strategic diagrams which propose a flexible framework for the key interventions to deliver them. These key principles are:

- Make the city centre more of a people place that transforms perceptions for visitors, citizens and investors.

- Recalibrate the balance between vehicles, pedestrians and cyclists as a major step towards improving the quality of experience of the city’s streets and spaces.

- As a key initiative to deliver this, introduce an integrated network of continuous pedestrian and cycle priority routes, Avenues, to connect key areas and transport nodes and link the City Centre with the surrounding neighbourhoods.

- Create Portals around the perimeter of the City Centre to make it easier for pedestrians and cyclists to cross barriers, such as the M8, and to make positive links with the surrounding neighbourhoods. e.g. Phoenix Flowers project by 7N Architects and RankinFraser.

- Manage vehicle displacement through a multi-modal movement strategy to ensure that the accessibility of the City Centre is maintained.

- Re-examine the designation of uses in specific areas where single uses may be inhibiting placemaking and perceptions.

- Make much more of the Clyde riverfront. Instigate specific projects to make it more integrated with the City Centre to encourage more use and development and linkages to the south side of the city.

- Build on current initiatives, developments and funding streams to link initiatives (e.g surface water works and green/blue infrastructure) and optimise the benefit of expenditure and investments.

- Develop designated City Quarters within the City Centre to focus initiatives on specific neighbourhoods and character areas and inform planning policies for the next iteration of the City Plan.

- Use the Avenues as the binding mechanism to integrate regeneration and placemaking initiatives within each City Quarter and throughout the City Centre and as a visible and tangible demonstration of the city’s intent to transform the quality of the environment for its future wellbeing.

- Integrate all of these initiatives with the other strands of the City Centre Strategy to form a cohesive, tangible, and inspiring Action Plan to deliver the Future Glasgow Vision.

The strategy deliberately sets out to be a framework of ideas that encapsulate key initiatives for transformational change rather than specific proposals at this stage. Its purpose is to establish the “big picture” to form a cohesive, co-ordinated, city wide strategy that will, in turn, inform more detailed studies. It needs to be flexible enough to be incrementally delivered over a long period of time and robust enough to keep the key principles and vision intact through the extensive negotiations that implementation will inevitably involve.

“If Glasgow can become a safer place to ride a bike then a whole range of other things will be delivered by default, from improving the pedestrian experience, to increasing footfall for retailers, to enhancing the city centre as a quality business destination. ”

Although the George Square debacle has been a setback in civilising Glasgow’s city centre the development of the strategy into an Action Plan and Planning Policy is already underway and some catalyst initiatives are beginning to come forward. Initiatives like Gehl Architects’ temporary colonisation of streets in Manhattan have been looked at as a way to test support as a precursor to permanent improvements. There is a chance that something like this may be put in place in the summer of 2014 to catch the spirit of the carnival atmosphere that will come with the Commonwealth Games. DRS are also moving forward with the 5 Streets initiative, in partnership with greenspace scotland and SEPA, to explore retrofitting green infrastructure in five city centre locations.

In the meantime, the temporary kids’ play area in the recent Merchant City Festival by Icecream architecture is one, positive, small step towards making the city centre more attractive to children and families. This is important to transforming perceptions as encouraging families back into the city centre will have a civilising effect on what can often feel like an intimidating environment. Of course cycle lanes and avenues are not the answer in their own right, and the strategy shouldn’t be seen as some kind of cycle lobby manifesto. But the use of bikes is perhaps an important measure of the civic wellbeing of the place, the canaries in the urban mine if you like, which London has proved over the last ten years.

If Glasgow can become a safer place to ride a bike then a whole range of other things will be delivered by default, from improving the pedestrian experience, to increasing footfall for retailers, to enhancing the city centre as a quality business destination. It would also play a small part in beginning to turn around the enormous challenges presented by Glasgow’s health issues.

The picture above of the guy riding through fountains was taken in Copenhagen this summer. It was a scorching hot day and I had stopped as my son wanted to splash around. As I was watching him the man on the bike swooped into the square, shirtless and with a guitar case on his back, and just rode straight through the columns of water to cool off in an impromptu shower. He did a couple of circuits ducking his head into the plumes of cool water and then just rode off again to continue his journey. It felt so natural, relaxed and unencumbered by convention that it made me think that a city environment that encourages adults to act like that is a good place to be.

Perhaps a measure of the success of Glasgow’s city centre initiative in many years’ time should be that the defining image should be akin to the man riding through the fountains rather than the anxious woman in Union Street. If the city centre can become a place that adults feel relaxed enough to spontaneously act like kids then that will be a real step forward.

This article first appeared in Urban Realm, Autumn 2013