The existing Fraser Avenue estate, originally built in 1956, is ranked in the top 15% of the most deprived areas of the country, according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation. Since its original construction, in a way not dissimilar to many post-war housing estates across Scotland dating from the same era, the community has both thrived and then struggled. In recent decades the estate has faced significant challenges in retaining its once strong community spirit, with a stigma taking hold in the wider community against those living on the street. It has become known locally as a ‘dumping ground’ for the local authority with new residents having little or no connections with the area. This has resulted in issues that have led to a distinct lack of civic pride and sense of community.

Following the completion of an options appraisal back in 2011 which looked at the future of Fraser Avenue, the decision was taken for the full demolition and complete redevelopment of the street. 7N Architects were subsequently appointed by Fife Council in 2014 to move the regeneration forward, working in close collaboration with the community and developing a strategy with local stakeholders that would transform perceptions and rebuild a strong sense of place and community.

In form the estate is essentially a linear street of 234 3-storey blocks of flats running north to south and bounded to the west by Spittalfield, a neighbourhood dating from 1924 and by Spencerfield to the east, another estate built in 1968. Our initial assessment of the existing street identified that the continuous frontage over such a long distance isolates Fraser Avenue from the surroundings and creates a “canyon” like feel. Public space is undefined with ambiguity over what is public or private, leading to little sense of ownership or belonging. The existing buildings are in poor condition with no definition of fronts and backs and the existing frontages to the streets and public spaces are hard and alienating. Many of the existing routes are not overlooked and do not feel safe for the residents. Existing parking courtyards to the rear of the blocks of flats form large expanses of hard, ill-defined space. However, the existing estate is home to many families, some of which have lived on the street for their whole lives.

The challenge therefore was to deliver transformational change without fragmenting the existing community. The reimagined Fraser Avenue needed to be woven into the social and physical fabric of the wider area, in order to break free from its image as an isolated, stigmatized street. The process needed to cultivate a greater level of social cohesion and sense of ownership.

“Like many post-war housing estates across Scotland dating from the same era, the community has both thrived and then struggled.”

Community Engagement

Working in collaboration with Nick Wright Planning, a series of visioning workshops and consultation events were held with the local community to establish key principles and a vision of what kind of place a reimagined Fraser Avenue might be. A number of options were subsequently developed based around the principles of shorter, more intimate streets where everyone would have their own front door and private garden. A mix of house types was desired to cater for a range of people with good quality building stock providing warm, dry, secure, energy efficient homes. Safe walkways, roads and cycle paths were needed with well cared for public space where kids could play. Lastly, the existing local shops were to be retained and relocated to work better within the wider community.

Of the various options tabled, the fundamental idea of realigning the existing street gained wide support. Not only did this provide a fresh start for Fraser Avenue by literally erasing the street and the stigma attached to it, but it also allowed a new central ‘village green’ to be proposed, creating a local heart for the community. It also meant the existing large expanses of undefined parking areas could be activated and incorporated into the new development area, allowing the new streets to connect into the existing network of paths feeding into the site from the surrounding neighbourhoods.

“A series of visioning workshops and consultation events were held with the local community to establish key principles and their vision of what kind of place a reimagined Fraser Avenue might be”

Phasing

From the initial client meetings it became immediately apparent that the implementation of the overall regeneration strategy was going to involve complex work associated with the decanting of existing residents to facilitate the phased demolition and construction of the Fraser Avenue estate. As a result of the long term stigma associated with the area, many of the existing flats had remained unfilled, meaning the existing tenants were dispersed across all of the blocks. This has required extensive consultations and negotiations to rehouse many of the tenants in the short term to free up blocks of flats to allow demolition to take place.

This dialogue has been assisted by the ongoing consultation on the new dwellings where, despite the requirement to rehouse families, they have been able to fully understand and appreciate the situation and have been able to view this against the backdrop of the creation of their eventual new homes. The regeneration programme is to therefore be split over 5 phases of demolition and construction which will be spread out over the next 5 years.

Garden City Principles

An inspiration for us was the little known Rosyth Garden Village less than a mile away, designed by Greig & Fairbairn and AH Mottram and completed in 1916, which was recently listed as one of the 100 best buildings in Scotland in the last one hundred years. Based on the principles established by Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City Movement from the turn of the 20th Century, it heralded a new approach to much of Scotland’s public housing in the twentieth century.

In response, the intention was to form a new garden suburb development of comfortable, lower density, secure new terraced homes for existing residents with private front and back gardens, well planned open green space within easy walking distance and open tree-lined public streets. In acknowledgment of the failed model of 3-storey communally accessed blocks of flats and undefined public realm currently occupying the site, the new urban approach sought to transform the area by creating an integrated and cohesive new place, woven into the network of existing streets and pathways surrounding the site to improve connectivity and increase permeability.

“An inspiration for us was the little known Rosyth Garden Village less than a mile away, designed by Greig & Fairbairn and AH Mottram and completed in 1916”

Terrace Typology

The orthodox approach for the redevelopment of a suburban environment such as Fraser Avenue would be to form a series of detached and semi-detached dwellings, normally accessed directly from a linear street which is often structured around the cul-de-sac typology. In fact, the blueprint for the regeneration project could have followed that taken on the adjacent street where the former Barr Crescent, now known as Caldwells Court, was redeveloped along these principles. Barr Crescent was to all intents purposes a miniature version of Fraser Avenue and it was clear that both the client’s and the community’s initial perceptions were to follow this model for the regeneration project.

However, with the demolition of 234 flats on Fraser Avenue and the need to rehouse many of the existing tenants in the new homes, a terraced housing typology has been employed to ensure a sufficient degree of density for the site. The use of terraces was also borne out of an analysis of the surrounding context, especially to Spencerfield where rows of terraces with private front and back gardens are arranged around a series of interconnected courtyards. However, where a lack of legibility exists between fronts and backs at Spencerfield, the emphasis for the new masterplan places importance on active streets and active frontages with clearly defined public and private space through individual front doors, purposeful front gardens and secure and private back gardens.

Terraces have been arranged to mediate between a new primary structure of streets that stitch into the existing road network surrounding the site, and secondary, more intimate shared surface news streets. The layout seeks to open towards the sun and harness the sloping topography for views south to the Firth of Forth, the Bridges and the Pentlands beyond.

Architectural Character

Whilst acknowledging an authentic new language for the new buildings, a limited palette of brick colours has been used to link in to the surrounding found fabric in Inverkeithing. The red brick connects to the 1930s housing at Spittalfield to the west and light grey brick acknowledges the grey harling used extensively on the 1980s housing at Spencerfield to the east. The use of coloured pantile roofing materials was inspired by Inverkeithing’s location as part of a string of historic towns along the coast of Fife. The pantiles echo the use and character of much of the historic building stock in villages like Culross to the west and the celebrated fishing communities of Crail and Pittenweem in the East Neuk.

The roof forms also have a dual purpose. They act as a device to reconcile the sloping topography of the site, by integrating steps in the floor levels of the terraces, and as a means to unify the varying storey heights of the different unit types within the more singular built forms of the terraces. They also mediate between the various forms of the surrounding context – the steep pitched roof forms of the terraced houses on Spittalfield and the low stepped roof forms of Spencerfield. The forms of the terraces are also enriched by the diversity of dwelling types required to rehouse the existing tenants – the units range from 2 bed ground and upper villa flats, to 2, 3, 4 and even 6 bed houses, as well as various amenity units and wheelchair bungalows. The various dwelling types are also contained with either 1 storey, 2 storey or 3 storey forms. In factoring in the varying unit layout types there are as many as 24 unit types within the 53 units being constructed as part of the first phase of development. To minimise the concentration of any single house type or family size within a particular terrace, the dwelling types have been actively distributed across the site and terraces, thus ensuring gentle deviations of form across all of the terraces, ensuring no single terrace shares an identical architectural language.

Within the common parameters of form and material constraints, it is hoped that this will create a distinctive new identity for the place, whilst still presenting a ‘terraced house-like’ image of domesticity. In this way the new dwellings will be reminiscent of our inherited suburban environments, linking into our wider cultural memory.

“Terraces have been arranged to mediate between a new primary structure of streets that stitch into the existing road network surrounding the site, and secondary, more intimate shared surface news streets.”

Inhabitation and Comfort

In reaction to the currently prevalent approaches to models of affordable housing across Scotland’s suburban communities, we have sought to harness the principles the Smithsons termed ‘good ordinariness’, and have placed inhabitation at the heart of our thinking for the creation of the new homes. An ongoing reference in this regard has been Christopher Alexander’s ‘A Pattern Language’ of 1977 and his thinking on building and planning. We have sought to place importance on the everyday - physical ease, privacy, intimacy, convenience and the idea of comfort – the notion of domesticity and the interior life of the house and its inhabitants. We have been motivated by the creation of this sense of comfort and the wellbeing of the people who will live in these new homes.

In the designs for the new terraces, fronts are treated more formally with the zone between streets defined by a semi-landscaped zone housing parking and individual bin stores which are integrated into garden walls defining each plot. Individual front doors are accentuated by these garden walls wrapping up to support profiled projecting entrance canopies. Openings are formed in these walls to engage with the proximity of adjacent units and emphasize neighbourliness. To the rear, the treatment is less methodical, responding to the interior planning and opening out towards the sun. High level garden walls provide privacy to the terraces immediately at the building line, with the fences then stepping down to a lower level at the soft landscaped gardens to allow for interaction and encourage a greater sense of community. Entrances to upper villa apartments are located onto the gables of the terraces to activate the end conditions and animate the elevations onto the adjacent streets.

The internal planning of the new houses adheres to the requirements of Housing for Varying Needs, the mainstream concept for determining affordable housing layouts. However where possible we have sought to think beyond the purely functional to create looser configurations that respond to the particularities of the immediate context and unit type. Flexibility of layouts have therefore been provided with each tenant choosing between a more traditional ‘closed plan’ layout of individual rooms and an ‘open plan’ layout where spaces flow into each other to provide the potential for views through the dwellings from front to back. There is also in-built flexibility where utility rooms or accessible bathrooms can be incorporated where required or desired. The resultant choices of layout configuration will form a ‘natural’ variation to the units along a terrace, providing a greater degree of richness to the life of the street. The tenant choice even extends from entrance door colours through to kitchen designs and shower screens, meaning the occupants are encouraged from the outset to assume a sense of ownership and inhabitation, creating an individuality to the interior life of each new home.

Kingdom Housing Association deserve great credit for adopting this as an approach – the idea that new affordable housing can be conceived as being tenure-blind, where there is no differentiation between the approach taken for private for sale housing and subsidized rented housing.

“In reaction to the currently prevalent approaches to models of affordable housing across Scotland’s suburban communities, we have sought to harness the principles the Smithsons termed ‘good ordinariness’, and have placed inhabitation at the heart of our thinking for the creation of the new homes.”

Public Realm and Landscape

Careful consideration has been paid to the public realm to address the poorly defined spaces that have contributed to the decline of the area in recent years. The designs aim to create a safe, comfortable and enjoyable place to live with materials that are robust, easy to maintain and responsive to the context.

New nodes are to be formed at key points along the new network of streets which will slow traffic and form shared surfaces for safe passage of pedestrians and cyclists. Dwellings are arranged around these nodes to provide overlooking and to create the feel of small scale ‘town squares’. New pocket parks are proposed along the eastern edge to reinvigorate existing open grasses areas. These are being designed in collaboration with the local community to provide a network of more intimate spaces for play beyond the main ‘village green’ as the centerpiece of the newly invigorated neighbourhood. A network of new structured tree planting is interlaced within the new street layout, which will soften the street scene, enhance spatial qualities and increase amenity.

A Traced Railway Line

The importance that the coal mining industry and the local collieries and miners clubs had on West Fife is hard to overstate. Whole communities grew out of the industry and, despite the evidence of the mines having now largely vanished, their impact still hangs over the collective memories of the people and communities of the towns and villages of the local area.

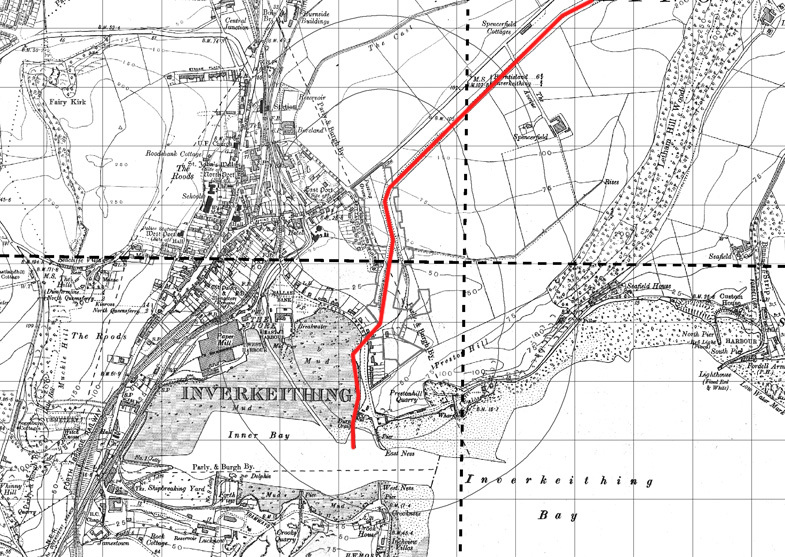

Prior to the construction of the Fraser Avenue estate in the 1950s, the site housed the line of the old Halbeath Railway, a narrow gauge railway dating back to 1780 that connected Halbeath Colliery on the edge of Dunfermline to the north and the pier in Inverkeithing’s inner bay to the south. Remnants of the lines route and associated infrastructure are still visible in the wider context.

As part of an integrated approach to public art work, the former line of the railway is to be traced across the site in the form of an imprinted concrete feature, recessed into the new network of paths and streets as it tracks from north to south. It will disappear and reappear as it passes from public realm to the private realm of the new houses and gardens, suggestive of the interconnection between the new and the old. It will be inscribed with the names of some of the key places, companies and routes that the line served and connected to: Halbeath, Dunfermline, Townhill; a physical reminder of the town’s strategic importance in the history of the coal mining industry in West Fife.

“As part of an integrated approach to public art work, the former line of the railway is to be traced across the site in the form of an imprinted concrete feature, recessed into the new network of paths and streets as it tracks from north to south.”

Building Fabric and Sustainability

The new terraced housing has been designed in compliance with the Silver Level for Section 7 - Sustainability relative to the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2015. This is an enhancement on the base level of the Regulations and offers substantial benefits in a range of sustainability aspects. The renewables strategy also includes for integrated photovoltaic panels to roofs to achieve a power peak of 0.5kWp.

Beyond this, the construction approach for the new houses takes on the ‘fabric first’ principle, aiming to maximize the air-tightness and the thermal efficiency of the building fabric. A recent research study conducted by Glasgow School of Art into the quality of ventilation in new build homes has found that many fail to meet the minimum standards for air quality. With increasing air-tightness levels, the links between poor ventilation and ill-health are being increasingly acknowledged where the build-up of CO2 and pollutants and chemicals in the home are having serious health effects, including conditions like asthma.

The fabric has therefore been developed to allow the process of ‘breathing’ to occur through the use of vapour open breathable wall constructions for the housing. This removes the use of plastic vapour barriers within the construction, which traps moisture inside the building interiors. The insulation products have been selected to be non-toxic materials with the timber frame structure insulated both between the studs and externally to minimize the cold-bridging of the timber kit. Moisture can therefore escape through the walls and roofs without condensation occurring inside the construction and similarly can allow moisture to migrate into the building if the internal climate is too dry, thus creating a more stable and healthier internal environment. The result is that the buildings will be kept warmer for longer in cold weather and cooler in hot weather, they will be quieter in terms of acoustic performance and will be dry and breathable, ensuring the long term health of the building fabric, something that is normally completely overlooked by most conventional insulation systems. The result is a highly insulated envelope with a low embodied energy, achieving U-values of 0.11W/m2K for roofs and 0.17W/m2K for walls.

The Future

Following Planning Permission in Principle approval in April 2016 for the wider illustrative masterplan, the subsequent Approval Required by Conditions consent was secured at the beginning of this year for the first phase of the regeneration. This will see the creation of 53 new affordable homes with a further 136 new homes and shop units with associated landscaping and infrastructure following on over another 4 future phases. The demolition of the initial blocks of flats was completed earlier this month and construction works have now commenced. The project has provided a rare opportunity to work on a regeneration project from first principles, working from the urban scale through to the scale of a window detail.

It is hoped that the approach taken for the regeneration of Fraser Avenue can act as a tangible model for the delivery of new and replacement affordable housing, where an inspiring approach to the reimagining of existing post-war settlements can transform towns and suburban environments across Scotland. With long term trends indicating that the affordability of housing continues to worsen relative to average earnings across the country, developments such as this can assist in giving locals and incomers the chance to rebuild and reinvent communities together. Through a socially-focused approach to transformational change in estates such as Fraser Avenue, the ambition is to break from the stigma of the past to create places populated by people who want to put down roots and feel invested in the communities in which they live. In this way, our existing settlements can be reinvigorated from within to instigate cohesive, socially successful communities that have the potential to thrive in the longer term.